As a satisfied owner of a shiny new Apple Airport Extreme (Simultaneous Dual-Band) Base Station, I am sharing my configuration and observations for interworking with O2 Home Broadband (not the O2 Home Access product).

The new AEBS can operate on both the 2.4GHz and 5GHz bands for 802.11n WiFi and the ability to migrate wireless traffic onto the less congested 5GHz band will provide significant improvements to data throughput.

For this (and many other) reasons it is advantageous to use the AEBS to manage your local network for WiFi and firewalling, in preference to the O2 supplied Thomson router. The AEBS is not an ADSL modem however and so you will still need your O2 router to connect to the BT network.

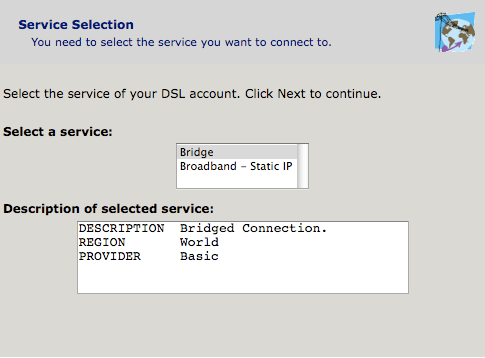

O2 Broadband Router Settings

Login to your O2 Wireless router and re-configure the device as an ethernet bridge:

O2 wireless box III > Configuration > Set Up > Bridge

When the router has rebooted, login again (http://192.168.1.254/) and disable the WiFi network interface:

Home Network > Interfaces > WLAN > Configure > Interface Enabled: No

Now connect your AEBS WAN ethernet port to an ethernet port on the O2 Home Broadband router.

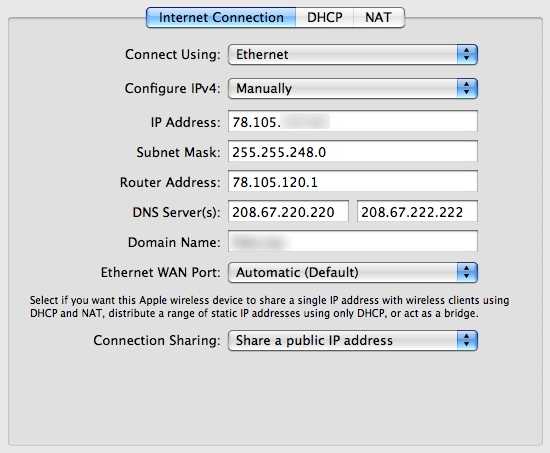

AirPort Extreme Settings

- Internet | Internet Connection

Connect Using: Ethernet

Configure IPv4: Manually (for static IP)

(For dynamic IP set ‘Configure IPv4: Using DHCP’ and ignore the next three lines)

IP Address: <provided by O2>

Subnet Mask: <provided by O2>

Router Address: <provided by O2>

DNS Server(s): 208.67.220.220 & 208.67.222.222 (these are the OpenDNS servers)

Domain Name: <your domain name>

Ethernet WAN Port: Automatic

Connection Sharing: Share a public IP address

Select an appropriate DHCP range for your network, or simply replicate the previous O2 Home Broadband router settings:

DHCP Beginning Address: 192.168.1.64

DHCP Ending Address: 192.168.1.253

DHCP Lease: 24 hours

Enable NAT Port Mapping Protocol

Local network

When you choose to ‘Share a public IP address’ and create a DHCP network from the RFC 1918 private network range, the AirPort will automatically reserve the first available IP address in the network range for itself.

e.g. if you are using 192.168.1.64 to 192.168.1.253, the internal network interface of the AEBS will be assigned the IP address 192.168.1.1. This is also the default route and domain name server for clients on your internal network.

AirDisk Sharing

From experimentation I have determined that sharing a connected USB hard disk via MobileMe only works if you configure your AEBS in the network configuration described above. The disk will not be accessible outside of your local network if your O2 broadband router is configured with your external IP address.

It is also necessary to activate ‘Back to My Mac’ on the machine that you are accessing from, even if you aren’t going to access this machine remotely.

System Preferences > MobileMe > Back to My Mac > Start

Remote Management

When signed into MobileMe from your Mac and with ‘Back to My Mac’ enabled, the Airport Utility software will discover remote AirPort devices signed into the same MobileMe account. It will allow you to select and configure the device in the usual way, just like being on the local network.